Eluiza and I spent the Second Sunday of Advent in La Chaise Dieu, about 25 km (15.5 miles) from Le Puy. This small village hosts a Benedictine Abbey that was founded a thousand years ago by Robert de Turlande.

We arrived at the chapel early enough to attend Sext, the mid-afternoon prayer of the Divine Office, followed by the Mass. The abbey is now run by the Brothers of St. John, and we chanted or sang almost every part of both the Office and the Mass, which was 90 minutes long--and included incense. It was beautiful and meditative.

Upon reflection, I realized that this sacred experience moved me greatly because we were praying old prayers in an old monastery whose very walls have witnessed prayer through the centuries. It also came from the enduring presence of God in a remote place where some small group of people have remained faithful to the traditions and prayers of the Church--despite all the troubles this place has seen: war, famine, poverty, pestilence, revolution, even secularization.

So, here is an historical tour of the abbey that helps to explain its significance and mysteries.

A Little History

|

| Statue at the Abbey of St. André de Lavaudieu |

Pope Clement VI became a monk at Chaise Dieu in 1301 at the age of 10. He became pope in 1342 and a patron of a much-expanded abbey church (built between 1344-1350), which became the setting for his entombment in 1352. He was the fourth Avignon pope (1342-52) and reigned during the Black Death (1347-50). He granted remission of sins to all who died of the plague.

Pope Clement VI became a monk at Chaise Dieu in 1301 at the age of 10. He became pope in 1342 and a patron of a much-expanded abbey church (built between 1344-1350), which became the setting for his entombment in 1352. He was the fourth Avignon pope (1342-52) and reigned during the Black Death (1347-50). He granted remission of sins to all who died of the plague.

|

| Statue at the entrance of the abbey church with a disfigured face |

During the French Revolution (1789-1799), the abbey was secularized, and the monks were driven out. Only the abbey church, Clement's tomb, and the abbey cloister remained. Some of the figures in the abbey, however, were disfigured, especially the heads of statues, which were lopped off in anger against the Church because it was closely allied with the monarchy. This part of the abbey's history is also retained.

During the French Revolution (1789-1799), the abbey was secularized, and the monks were driven out. Only the abbey church, Clement's tomb, and the abbey cloister remained. Some of the figures in the abbey, however, were disfigured, especially the heads of statues, which were lopped off in anger against the Church because it was closely allied with the monarchy. This part of the abbey's history is also retained. |

| Headless wooden figures on the choir stalls |

|

| marred face of a bishop's tomb |

Today, the abbey is a working parish that is run by the Brothers of St. John. It hosts several projects such as the Chaise Dieu Music Festival in August where thousands of people come to listen to sacred music as well as a classical and a contemporary repetoire. Year-round, the abbey opens its doors to celebrate its history with the Danse Macabre frescoes that commemorate the plague (1347-50) that decimated one-third of Europe's population at the time. Last summer the abbey hosted tours of the newly-restored tapistries that formerly hung in the monks' choir. The town of Chaise Dieu itself has undertaken various renovation projects of the abbey's old buildings, which began in 2007 and continue today. This blog discusses some of these special features of the abbey.

The Black Death and the Danse Macabre

One of the remarkable art pieces in the abbey are the frescoes of the Danse Macabre. The dance is series of skeletons leading those represent the various stations of medieval life in a religious ritual procession to the grave. During the late Middle Ages in western Europe, the dance was an allegorical concept signifying the all-conquering and equalizing power of death.

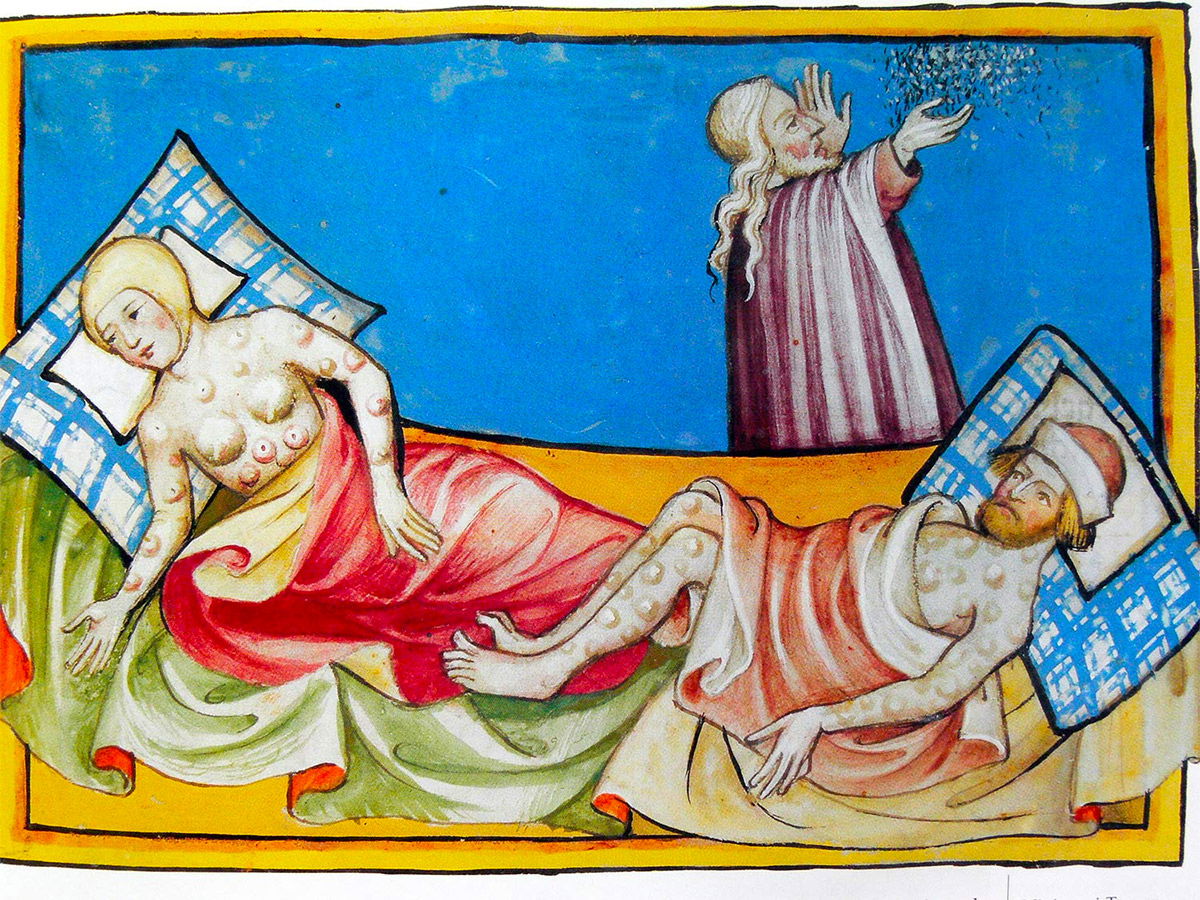

Miniature out of the Toggenburg Bible (Switzerland) of 1411. The disease is widely believed to be the plague, although the location of bumps and blisters is more consistent with smallpox.

The Danse Macabre (The Dance of Death) specifically reflects the traumatic event of the Black Death (1347-50) where 50 million Europeans died of the Bubonic plague. The effects of such a large-scale shared experience on the population influenced poetry, prose, stage works, music and artwork throughout the period, as evidenced by writers such as Chaucer, Boccaccio, Petrarch and artists such as Holbein.

The frescoes of Chaise Dieu are among those few in Europe illustrating the Danse Macabre. The 23 figures are about a meter high. Death comes in the form of stylized skeletons, sometimes wearing a shroud. The skeletons dance and invite each figure to Death. The dance is macabre because its invitation is to people who do not wish to die, but who must join the dance.

This artistic form began as religious theatre acted out by Franciscans. It was later depicted on walls and in published form starting in 1484.

The frescoes of Chaise Dieu were done in 3 panels like this one around 1484 by an unknown artist.

Text accompanied each figure, but most of them have been worn away with time with parts missing (signified with .... marks). Below are selected characters of the frescoes with explanations of them provided by the abbey.

The Commentator

The Commentator

On the first pillar, half-erased, he is seated in his chair and begins the Dance:

“Oh reasonable being

Who wishes for eternal life You have here the remarkable doctrine

Of how to end your mortal life well

The Death Dance reminds us That each of us has to learn to dance

Both men and women naturally

Death spares neither great nor small.”

The lesson is clear: listen to the teaching and you will surely go to Paradise

when you die. The text continues: “You can see it begins with the most important ...”

First Panel

The Pope

Death is rather respectful to him; he is going in the right direction and death only needs to nudge him gently from behind.

The Constable

Death takes a firm hold of the Constable (in the beautiful armour), commander-in-chief of the king’s armies. While the military man replies that he would like to assault once more “the castles in order to gain honour and riches," alas “all prowess, Death brings low”.

Death takes a firm hold of the Constable (in the beautiful armour), commander-in-chief of the king’s armies. While the military man replies that he would like to assault once more “the castles in order to gain honour and riches," alas “all prowess, Death brings low”.

Second Panel

The Merchant

The person with a well-trimmed beard wearing a beautiful hat, rich clothes, taking a firm stance is a merchant, without a doubt skillful in business, as indicated by the full money bag at his belt; he seems to be looking down on Death, no doubt certain of obtaining, thanks to his skill, a reprieve. Death does not negotiate but with a large smile, extends his arm to let him know the imperative of taking “the right path".

The Royal Justice Officer

The Royal Justice Officer He has a wide-brimmed hat, his truncheon and the fleur de lyson on his uniform. He has a military bearing and certainly knows how to get people to obey him; at first glance, everything should fall into place for him. But he is overwhelmed. On one side he is disarmed by mockery, and on the other, he is being led away. Powerful officer that he is, (shown by his already bent knee), he is forced to obey.

The Elegant Squire

In the third panel, the first person is an elegant squire with curly hair, a beautiful topcoat with long sleeves and his pony-skin shoes, immobilised because Death has dropped a poesy of flowers for his belle ... He thinks only about seducing female hearts ...

The Doctor (center)

He is from the Sorbonne, blinded by his bonnet, having no clear view of reality or truth. Moreover Death points an accusing finger at the parchments hanging from his belt, no doubt full of errors, not to say heresies. Perhaps his teaching is like the rattle which Death is shaking in his ear.

The Troubadour (to the right of The Doctor)

The one in the beautiful clothes has lost his sense of humor and in his chagrin has smashed his hurdy-gurdy when faced with death.

In the third panel, the first person is an elegant squire with curly hair, a beautiful topcoat with long sleeves and his pony-skin shoes, immobilised because Death has dropped a poesy of flowers for his belle ... He thinks only about seducing female hearts ...

He is from the Sorbonne, blinded by his bonnet, having no clear view of reality or truth. Moreover Death points an accusing finger at the parchments hanging from his belt, no doubt full of errors, not to say heresies. Perhaps his teaching is like the rattle which Death is shaking in his ear.

The Troubadour (to the right of The Doctor)

The one in the beautiful clothes has lost his sense of humor and in his chagrin has smashed his hurdy-gurdy when faced with death.

The Peasant

Death catches the

peasant going in the

wrong direction (he moves to the right), the full

sack of grain on his

shoulder. He is very sad at

having to leave his fields

and his harvest, to which

he was too attached. In his

chagrin, he lets his

scythe fall ...

Death catches the

peasant going in the

wrong direction (he moves to the right), the full

sack of grain on his

shoulder. He is very sad at

having to leave his fields

and his harvest, to which

he was too attached. In his

chagrin, he lets his

scythe fall ...

Death catches the

peasant going in the

wrong direction (he moves to the right), the full

sack of grain on his

shoulder. He is very sad at

having to leave his fields

and his harvest, to which

he was too attached. In his

chagrin, he lets his

scythe fall ...

Death catches the

peasant going in the

wrong direction (he moves to the right), the full

sack of grain on his

shoulder. He is very sad at

having to leave his fields

and his harvest, to which

he was too attached. In his

chagrin, he lets his

scythe fall ...

The Little Child

Finally, seeming shameful, Death hides its face with a veil and hunkers downward while coming for a little child (wrapped in swaddling clothes as they were at the time). This is understandable. According to classical texts, Death has compassion for this infant who is afraid and tells it “in the world, you would find little pleasure.” More deeply, Death does not wish to frighten the child at this moment of good news where the child is going to avoid a life of suffering with Death leading it to Paradise. In fact, for this little, baptised infant, it will be Heaven, immediate eternal happiness, as the Christian faith affirms.

“Death” more alive than the living?

Perhaps this is the way we should interpret this particular presentation of Death at La Chaise-Dieu. As Death here is not a hideous skeleton holding a scythe, pike-staff, or lance, as it does elsewhere. It is not represented as harsh or violent, even if it is incorruptible, since the reality of Death is inevitable. It kills people certainly, but it dances, leaps and capers. It is so lively that it evokes life in Heaven. It seems to say that life does not end in death. At Chaise-Dieu, the liveliest thing is Death, not those living in this world. Perhaps the message is that life here below can be the doorway to a life full of happiness and joy in the presence of God. This interpretation brings us back to the introduction of La Danse Macabre:

Finally, seeming shameful, Death hides its face with a veil and hunkers downward while coming for a little child (wrapped in swaddling clothes as they were at the time). This is understandable. According to classical texts, Death has compassion for this infant who is afraid and tells it “in the world, you would find little pleasure.” More deeply, Death does not wish to frighten the child at this moment of good news where the child is going to avoid a life of suffering with Death leading it to Paradise. In fact, for this little, baptised infant, it will be Heaven, immediate eternal happiness, as the Christian faith affirms.

“Death” more alive than the living?

Perhaps this is the way we should interpret this particular presentation of Death at La Chaise-Dieu. As Death here is not a hideous skeleton holding a scythe, pike-staff, or lance, as it does elsewhere. It is not represented as harsh or violent, even if it is incorruptible, since the reality of Death is inevitable. It kills people certainly, but it dances, leaps and capers. It is so lively that it evokes life in Heaven. It seems to say that life does not end in death. At Chaise-Dieu, the liveliest thing is Death, not those living in this world. Perhaps the message is that life here below can be the doorway to a life full of happiness and joy in the presence of God. This interpretation brings us back to the introduction of La Danse Macabre:

“Oh reasonable being,

You have here the remarkable doctrine

Of how to end your mortal life well.”

Click here for a lecture on the Dance of Death available through YouTube.

New Life and New Purposes at Chaise Dieu

The massive 17th century pipe organ in the back of the church was pivotal in breathing new life and purpose into the abbey in the 20th century. Silenced since the French Revolution, the organ was discovered by the famous Hungarian pianist, Georges Cziffra (1921-1994) while he was visiting friends in Chaise Dieu. In 1966, he and his son, György Cziffra (1942–1981), a conductor, began offering recitals and concerts of sacred music to raise funds for restoring the organ. These efforts evolved into the Chaise Dieu Music Festival in 1976, which has been held every year at the end of August at the abbey as well as in churches Puy-en-Velay; the Église Saint-Jean d'Ambert and the Basilique Saint-Julien in Brioude; the Saint-Georges Church of Saint-Paulien; and the Saint-Gilles Church of Chamalières-sur-Loire. In addition to sacred music, the festival offers a romantic and symphonic repertoire and some contemporary music.

Close-ups of the two who hold up the organ on both sides.

King

David (left) overlooks the organ as he plays the Psalms on his lyre (harp).

St. Cecilia (right), the saint of musicians, is also present with her violin. And here is a sample of the organ's majestic music.

The sanctuary of the church is transformed into a stage for the choir and orchestra during the Music Festival.

The sanctuary of the church is transformed into a stage for the choir and orchestra during the Music Festival. Other Special Features of the Abbey

The bells call the people to worship at a Sunday Mass.

The Rood‐Screen (15th century) is made of stone and it separates the choir, which was reserved for the monks, from the nave. This is the space where the pilgrims and the congregation gathered. On the balcony the deacon read the Gospel during the Mass to the faithful below in the nave. A massive cross hovers over the rood screen and is aptly framed by the arches above it.

This area of the church features the altar and tomb of St. Robert of Turlande on the right side.

On the left side is an altar with the painting "Descent from the Cross." The painting is very graphic and emotional.

The sanctuary and altar of Chaise Dieu Abbey.

The Gothic-style arches end in a flattened roof with pillars that have no capitals. Known as the Languedocian style, the arches leave the pillars immediately like branches of a palm tree. The fineness of the octagonal pillars give a lightness to the structure.

This stone was used to wash the body of a deceased monk to prepare it for burial. The hole at the bottom of the stone drained the

water. A vigil was typically held

around the deceased monk body.

This stone was used to wash the body of a deceased monk to prepare it for burial. The hole at the bottom of the stone drained the

water. A vigil was typically held

around the deceased monk body. The choir is comprised of 144 oak stalls with figures of Vice and Virtue above and behind each choir seat on the second tier. The monks attended Mass and prayed the Divine Office in these stalls.

Above each stall is a carving of a monk presumably representing his character. Here are some samples:

The stalls have misericords, little half‐seats

on the upside edge of the main seat. When the seat is up, a monk chanting

the service may "half‐sit" if he is tired. In this way the seat

provides mercy or misericord, and he can continue to pray with some support to his "stance."

The monks prayed the Divine Office seven times a day (cf. Psalms 118 &

164). The Office was composed of 150 psalms spread over the week and took about six hours each day.

The stalls have misericords, little half‐seats

on the upside edge of the main seat. When the seat is up, a monk chanting

the service may "half‐sit" if he is tired. In this way the seat

provides mercy or misericord, and he can continue to pray with some support to his "stance."

The monks prayed the Divine Office seven times a day (cf. Psalms 118 &

164). The Office was composed of 150 psalms spread over the week and took about six hours each day.

During the French

Revolution, after 750 years of praising God, the Benedictine monastic

prayers ceased.

Then in 1984 at the

request of the Bishop of Le Puy, the Apostolic Sisters of Saint John religious community came and chanted the Office again

in the abbey church for about half the year. This same community of sisters serves at the Cathedral in Le Puy.

Tapistries

Above the

choir stalls is the place where a series of tapistries used to hang. These were embellished copies of the Bible of the

Poor that represented 26 scenes from the life of Jesus Christ. They are framed by scenes from

the Old Testament, according the principle where the

Old Testament is the New one hidden, the New Testament is the Old one unveiled. The tapistries were recently restored and brought back to the abbey last summer. They are now hanging in a chapel located

in the wing of the Echo chamber in another building of the abbey. Here is a selection of reproductions from among the tapistries.

Above the

choir stalls is the place where a series of tapistries used to hang. These were embellished copies of the Bible of the

Poor that represented 26 scenes from the life of Jesus Christ. They are framed by scenes from

the Old Testament, according the principle where the

Old Testament is the New one hidden, the New Testament is the Old one unveiled. The tapistries were recently restored and brought back to the abbey last summer. They are now hanging in a chapel located

in the wing of the Echo chamber in another building of the abbey. Here is a selection of reproductions from among the tapistries. Restoration

Restoration is an obvious priority in Chaise Dieu as posters of work groups and actual scaffolding appear all over the city.

One of the building projects in Lafayette Square.

This gate and adjoining building were constructed in the 14th century. The building housed stables and barns. It was later transformed in 2009 into the Cziffra Auditorium and restored between 2012-14. The building's hydralic system will be restored over the next three years. This system was put in place in the 18th century to clear out waste water and to collect rain water.

This gate and adjoining building were constructed in the 14th century. The building housed stables and barns. It was later transformed in 2009 into the Cziffra Auditorium and restored between 2012-14. The building's hydralic system will be restored over the next three years. This system was put in place in the 18th century to clear out waste water and to collect rain water.

Restoration is an obvious priority in Chaise Dieu as posters of work groups and actual scaffolding appear all over the city.

One of the building projects in Lafayette Square.

This gate and adjoining building were constructed in the 14th century. The building housed stables and barns. It was later transformed in 2009 into the Cziffra Auditorium and restored between 2012-14. The building's hydralic system will be restored over the next three years. This system was put in place in the 18th century to clear out waste water and to collect rain water.

This gate and adjoining building were constructed in the 14th century. The building housed stables and barns. It was later transformed in 2009 into the Cziffra Auditorium and restored between 2012-14. The building's hydralic system will be restored over the next three years. This system was put in place in the 18th century to clear out waste water and to collect rain water.

The old stone retains the agelessness of the Earth from whence it came as it resides on the old buildings of the abbey.

La Chaise Dieu holds a thousand years of memory, and its significance today reveals that life is not ended, it is changed. Even desperate events like war, poverty, famine, pestilence, revolution, and secularization could not break the fortifications of a place dedicated to God. Chaise Dieu has lived up to its name as the "seat of God," and we are the fortunate witnesses of its life and majesty.

La Chaise Dieu holds a thousand years of memory, and its significance today reveals that life is not ended, it is changed. Even desperate events like war, poverty, famine, pestilence, revolution, and secularization could not break the fortifications of a place dedicated to God. Chaise Dieu has lived up to its name as the "seat of God," and we are the fortunate witnesses of its life and majesty.