We

started bright and early (7:30 a.m.) today for the long ride that

would take us across the Middle and High Atlas Mountains and to our

hotel for tonight in Erfoud where we arrived at 5:30.

I'm feeling much better after 10 hours of sleep last

night and 2 hours in the afternoon. I started out with a terrible

hacking cough, which two days ago developed into a cold. My sides

ache from all the coughing and my muscles ached. I have never been

this sick on a trip. But nothing was going to stop me from going to

the Medina in Fez or to make the home visit to a middle class family.

Actually, I welcomed the day-long trek through the

mountains not only for the beautiful natural sights, but for a rest

after all the activity we have had over the past few days. Yemni is

very thoughtful. He knows just when to take comfort stops and just

when to take a look at something along the way. We usually start out

our day between 7:30 and 8:30, but we end by 3 or 4 p.m. so that we

have some time to ourselves before dinner. Twenty years of guiding

work has given him this gift—and an uncommon patience with groups.

When we pack up and leave a place, he doesn't just say:

“Make sure you take everything with you.” He appeals to people

by saying: “Please, do this for me.” It would be difficult to

retrieve a forgotten item and it would waste a lot of time that we

don't have with our very full itinerary. He emphasized the importance of not leaving anything behind by letting us know that we would have to pay for the transport of a lost item. Miraculously, there were no incidents of lost or left behind items.

Then, while en route to a place, if Yemni sees

something interesting, he asks the bus driver to stop and we pile out

and look at it, like the other day when we stopped on the way to

Mekenes to talk with a woman who lived on the countryside—and

today, when we stopped in a cedar forest and took a walk of about 20

minutes. The air was brisk but fresh and there were few sounds

around us. The cedars were planted by the French and the present

government. The seedlings come from Lebanon. The cedar wood is used

for ceilings in mosques, schools, and other public buildings. There

are also oaks here and you can recognize them for their rounded

shape. The cedars look like triangular Christmas trees.

Then, while en route to a place, if Yemni sees

something interesting, he asks the bus driver to stop and we pile out

and look at it, like the other day when we stopped on the way to

Mekenes to talk with a woman who lived on the countryside—and

today, when we stopped in a cedar forest and took a walk of about 20

minutes. The air was brisk but fresh and there were few sounds

around us. The cedars were planted by the French and the present

government. The seedlings come from Lebanon. The cedar wood is used

for ceilings in mosques, schools, and other public buildings. There

are also oaks here and you can recognize them for their rounded

shape. The cedars look like triangular Christmas trees.As we entered the mountain lands we made a comfort stop in Ifrane. Also located here is Al Akhawayn University, a private university built by Hassan II, the father of the present king. It had red tile roof tops. Unlike the public universities that are free, private university student pay as much as 6,250 dh per month. They study in English and they have American professors. It is one of the best private universities, and students are assured a job if they finish. According to Wikipedia:

Al Akhawayn University (Arabic: جامعة الأخوين, meaning The Two Brothers' University referring to the King Fahd of Saudi Arabia, and the King of Morocco Hassan II) is a university located in Ifrane, Morocco, 70 kilometers from the imperial city of Fes, in the midst of the Middle Atlas Mountains.

The creation of Al Akhawayn University was largely funded by the King of Saudi Arabia from a large endowment intended for the cleanup of an oil spill off the coast of Morocco.[1] However, the cleanup was never realized as the wind blew the oil spill away and the endowment was used to create the university. Al Akhawayn University was founded by Royal Decree (Dahir) in 1993 and officially inaugurated by the former King of Morocco, Hassan II, on January 16, 1995.

Near the university is a ski town (a.k.a. "Little Switzerland") that was built by the French earlier in the twentieth century. Rich people hang out here, and the King has a palace on a hill nearby. This resort that looks like it was lifted out of the Alps of Europe and into Morocco is a big draw for a weekend jaunt, especially during the hot summers. The King of Morocco has a place in this area, too.There are a lot of empty homes in winter but the people flock here to cool off during the summer months. (This is the way it is in West Michigan, only we get Chicago people who spend their summers on Lake Michigan.)

At the entrance to the resort is a lion hewn out of the rock sitting there. It was sculpted by a man who was a prisoner at the time. Art and beauty, once again, triumph over someone's bad reputation.

The land is sparse of trees and vegetation, but a whole way of life exists in small clumps of people and sheep. It is the life of the semi-nomads. This life is quite a contrast to luxury and wealth of the people who hang out in "Little Switzerland," and we had a unique opportunity to stop and talk with some semi-nomads. These people are Berbers

(indigenous people who have occupied Morocco for 9,000 years) and unlike the nomads who live in the desert, semi-nomads move between two to three

huts per year and stay in this area of the Middle Atlas

Mountains. Their homes are made of wood with plastic covering. They

move from hut to hut to give their sheep new grazing areas.

|

| woven rugs provide warm seating on outer edges of the hut |

|

| wooden roof of the hut adds more permanence |

|

| entertainment center |

Their sale of their sheep earns them money to buy

the things they need, like the plastic mats they have placed

throughout the hut to walk on. Thick blankets line the perimeter of

the hut and we sat on them as we talked with them and received their

offering of homemade bread with olive oil and a small glass of mint

tea. They get rides to the town by hitchhiking a ride with passing

vehicles, like if they go to the market, the hospital or send their

child to public school. They also hire trucks to take their sheep

and donkeys to a new place rather than walk them there.

|

| Zeeda and son, 3 |

We met two of the young women of this nine-person family. Ermina, 26, is married with a daughter who is 4, and Zeeda is also married with a son, 3. They gave birth to their babies in Oserde where there is a public hospital. We did not meet any of the men because they were with the sheep. Their older family members live in town while the younger people live in the countryside in these huts.

School has been available to all the children of Morocco since the late 1980s and the semi-nomads take advantage of it, too. The adults want their children to go to school so they can get jobs. This means they would spare their children the hard life of the semi-nomad. Yemani was quick to add that although they have this wish for their children, not all are able to achieve this goal. So semi-nomadic life will not die out anytime soon even though there are fewer nomads today than there were 40 to 50 years ago.

Hospitality is an art a tradition and as an obligation extended to ALL visitors.

|

| bread and glasses of mint tea |

|

| barn and adjoining barnyard |

This family has two huts for living quarters, a corral and adjoining “barn” for the sheep. There is also a bread over; I'm not sure if it was outside or covered. They have sited their buildings on the side of a hill, probably to attain some protection from the wind. They gather wood for their stoves.

One of the many sheep herds we saw on the road. Sheep are the bread and butter of the rural Moroccan people.

The women were very welcoming to our group and they allowed us to take photos. I'm sure we were the subject at the dinner table that night.

To the Mountains

|

| Yeyahi Mountain |

The terrain before us is sand-colored and rocky and grainy. My ears are getting plugged up by the altitude, but I cannot pop them. Many of us find ourselves to be a little more tired than we started out the day. I think it's the altitude. There are some isolated houses and farms in these lands and the buildings are flat-roofed. There are also packs of wild dogs hanging out near the road. Truck drivers give them food from restaurants they eat at and that's why they are here.

I usually think of mountains as insurmountable

obstacles, but there are passages through them as well as valleys.

Here, there are several bare spots but more and more trees are being

planted. They are pleasant and welcoming. The mountains are a good

place for contemplation. I also notice that most of the mountains

are nondescript but as a group, they create an environment.

Take Me to the Kasbah -- for Lunch

Take Me to the Kasbah -- for Lunch

We stopped for lunch at Midelt, which is the apple

capital of Morocco. We had charcoal-baked trout that was supremely

delicious, along with vegetables—and French fries! For desert we

had bananas and clementines. So refreshing and tasty!! No chemicals

in this food and it was all local.

|

| reception area of the hotel |

|

| beautiful dining area |

| ||

| trout and french fries!! |

|

| every meal begins with soup |

This

town was built in the early 20th

century to support the apple economy. There is wilderness all around

us, but it is interesting to see settlements spring up out of nowhere

and to wonder why they did. One thing for sure, these wilderness

lands are alive—and throughout them there are lines of electrical

wiring. This was a project of the Labor Party Prime Minister who

sponsored a number of electricity and water projects in the country.

The electricity was paid for by the urban population with a 20 dh

addition to their monthly utility bill so the people in the country

would have electricity, too. Europe and Japan also helped subsidize

the project.

As we entered the Ziz River Valley area we stopped before a tunnel, which was built by the French Foreign Legion in 1939.

It was another break so that we could stretch our legs, take photos, and admire our beautiful surroundings.

This is a dam lake in this area, the Errachida, which is fed by the Ziz River. It is one of 75 dam lakes built in the 1960s for irrigation. The further south we went today, the more we would see date palms growing. It is a big industry. However, it is irrigation that makes the date palms possible as these arid lands could not grow anything with the little rain that is here. Date palms give birth to dates and little trees. After 6 years a date palm is able to bear fruit annually.

a water project in the making

Unfortunately, this year is a particularly dry year and

the lake was down by several meters. We could see that from the lime

“bathtub ring” on the sides of the lake's mountain walls.

Unfortunately, this year is a particularly dry year and

the lake was down by several meters. We could see that from the lime

“bathtub ring” on the sides of the lake's mountain walls.

When we crossed the High Atlas Mountains we began to

enter the desert region—and we were getting close to the highlight

of the trip, two days in the Sahara Desert. The Moroccan desert has

three types: stoney, sandy, and sand dunes. Most Moroccans (80

percent) live in the northern part of the country in the big cities

and towns. Here in the Ziz Valley it doesn't rain much and life is

limited. Saharan architecture appeared with flat boxes of mixed mud and

snow.

Inscribed on the mountain is the phrase "God, King and Country." Most towns display this motto near the entry way into the town.

We made a comfort station stop at a gas station near Errachida, an army town. The station resembled our Union 76 stations. There was a snack bar with a room full of slick, clean tables—and a couple seatings that looked like Moroccan style living rooms. Young teenage boys served the coffee. When someone ordered tea, they made it in the traditional way by pouring it high up into the cup to allow air to pass through it. The cafe au lait that I had hit the spot. The little store had snack foods and I bought a small can of Pringles and a Snickers bar. This was another occasion where Yemni anticipated our needs. The store also had a lot of change, which most stores are unprepared for. We need 1 dh coins every time we go to the bathroom so that we can give the attendant a 2 dh tip, as is the custom.

Errachida was quite developed. It was built as an army

town in the 1930s. There is an airport here and Saudis fly into it

so they can go hunting for obara, a bird that is as big as a chicken.

Hilary Clinton has been coming here since 2003. She has a sister or

an aunt who married a Berber and lives in Marrakech.

After crawling through the very flat, barren lands of

date palms and mud buildings, we made another picture stop on the

side of the road and found a man selling dates. He gave out samples

and offered a box of small dates for 20 dh ($2.50) and a box of large

dates for 120 dh ($15). I decided to buy a box and when Yemani saw

that, he suggested I buy the large dates, and I'm glad I did. They

had a small stone with a lot of meat around it and tasted so good.

The date is important to people in this region. The

After crawling through the very flat, barren lands of

date palms and mud buildings, we made another picture stop on the

side of the road and found a man selling dates. He gave out samples

and offered a box of small dates for 20 dh ($2.50) and a box of large

dates for 120 dh ($15). I decided to buy a box and when Yemani saw

that, he suggested I buy the large dates, and I'm glad I did. They

had a small stone with a lot of meat around it and tasted so good.

The date is important to people in this region. The

Muslims use it

to break their Ramadan fast.

Three more people in our group have contracted colds and/or coughs. This makes the trip more challenging, but everyone is keeping up with our itinerary. However, one women and her husband who accompanied her, would stay behind in Erfoud instead of going to the desert because she was not feeling well at all.

Last Stop Before the Desert

We arrived at our hotel, the Belere, about 5:30--just in time for the sunset. I was very impressed with this beautiful place. The Moroccans are trying to develop tourism as an economic development money-maker. And, they are very serious about this effort, as evidenced by this hotel. The desert is a big draw for travelers, and Erfoud is one of the last stops after the long trek through the mountains and just at the entrance of the desert.

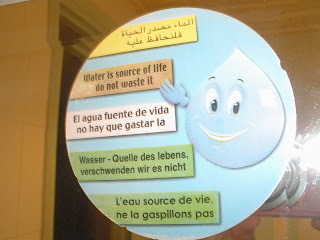

We arrived at our hotel, the Belere, about 5:30--just in time for the sunset. I was very impressed with this beautiful place. The Moroccans are trying to develop tourism as an economic development money-maker. And, they are very serious about this effort, as evidenced by this hotel. The desert is a big draw for travelers, and Erfoud is one of the last stops after the long trek through the mountains and just at the entrance of the desert.  This is my room. I'm getting to like these long couches that are commonly found in Moroccan houses and hotel rooms. I used this couch and table to write this blog entry. Since the hotel is on the apron of the desert, a poster in the bathroom reminds travelers that water is the most critical resource here.

This is my room. I'm getting to like these long couches that are commonly found in Moroccan houses and hotel rooms. I used this couch and table to write this blog entry. Since the hotel is on the apron of the desert, a poster in the bathroom reminds travelers that water is the most critical resource here.

Although we are staying only one night here in Erfoud, Yemni advised us on how to pack for our desert camp: take only what we need. Although we can bring our suitcases, a sandstorm would likely get into our cases. We need to wrap everything in plastic for this possibility. We will leave our suitcases on the bus where they will be safe and take seats in off-road land rovers that will take us to the desert and our campsite. We will live in canvas tents and OAT has asked the camp owners to provide indoor bathrooms since so many people get up in the middle of the night to use them.

It will likely be in the 30s at night, although the day time will be as warm and as balmy as we have been experiencing in Morocco so far. He also suggested that we put our mattresses on the ground rather than to sleep on the metal bed. It will be warmer. Several people expressed a little trepidation about the sand and the cold even though they have looked forward to this part of the trip as a highlight. Our ears were still popping from the altitude and that made hearing a little difficult, too. However, all will be well as we go through it. Yemani is there for us. That's comfort enough.

|

| Moroccan-style salad |

|

| delicious buffet supper |

I used the evening (and the time before dinner) to catch

up on this blog. My illness had prevented me from b

logging in as much as

I could and I still have a couple past days to write about. Maybe

I'll get some time in the desert—although I have to be judicious

about the computer's battery. I only have 3 hours available on it

and there is no electricity to recharge my machine in the desert.

This is going to be a unique experience!!

|

| tagine of beef, olives and prunes |