I first heard about Soweto at an intercultural communication conference. Dancers and singers played music that was deeply moving and haunting as it described the tragic uprising where black school children led a series of demonstrations and protests June 16-18, 1976. Police unleashed a firestorm against the kids and killed 176 of them with some estimates going as high as 700. At least 1,000 students were wounded. Since I was in Johannesburg for a couple days before my African safari, I had to go to Soweto.

About 20,000 students took part in the protests in Soweto. On June 17, the students were met with fierce police brutality as 1,500 officers carrying automatic rifles, stun guns, and carbines assaulted them. To break up the crowds, the police drove huge, menacing armored vehicles (at least twice the size of a man) while helicopters buzzed around the area from above.

The riots were a tipping point in the then 28-year fight against Apartheid as news of the riots spread around the world and sparked more focused and forceful opposition to Apartheid in South Africa. Soweto

residents would remain in the forefront of demands for Black

equality during Apartheid before and after the 1976 uprising--with years of violence and repression.

The riots were a tipping point in the then 28-year fight against Apartheid as news of the riots spread around the world and sparked more focused and forceful opposition to Apartheid in South Africa. Soweto

residents would remain in the forefront of demands for Black

equality during Apartheid before and after the 1976 uprising--with years of violence and repression.

Hector Pieterson, 12, is carried by Mbuyisa Makhubo

after being shot by the South African police. His sister, Antoinette

Sithole, runs beside them. Pieterson was rushed to a local clinic where

he was declared dead on arrival. This photo by Sam Nzima became an icon of the Soweto uprising and caused shock, outrage, and international condemnation on the Apartheid government. The photos below also illustrate the confrontations between residents and the police during the uprising.

The Soweto riots were subsequently depicted in different media like the 1987 film, Cry Freedom, the 1992 musical film Sarafina!, and the 2003 film, Stander. The riots inspired Andre Brink's novel A Dry White Season and a 1989 movie of the same title. The song, "Soweto Blues", by Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba describe the Uprising and the children's part in it. Here it is below.

The world denounced the South African government after the uprising, which subsequently advanced the process of abolishing Apartheid.

- The UN Security Council passed Resolution 392, which strongly condemned the incident and the Apartheid government.

- Many institutions--both corporate and non-profit--issued sanctions against South Africa through stocks and products.

- The South African government experienced a crisis in legitimacy because of its Apartheid policies and enforcement.

- The lack of police control over the

violence damaged the government’s standing among white South

Africans and further alienated non-white South

Africans.

- South Africa's reputation on the world stage sunk to low levels because of Apartheid.

- South Africa's exclusion from international sports competitions from the early 1970s until the early 1990s. Exclusion probably had the biggest psychological impact on the white population.

The uprising led to the adoption of a new constitution in 1993 that enfranchised all racial groups in the country.

In remembrance of the uprising, June 16 was proclaimed a public holiday in South Africa in 1991 and named Youth Day. Internationally, June 16 is known as The Day of the African Child (DAC).

Winnie Mandela House

It stands proudly on Vilakazi Street as a testament to the struggle for equal rights and freedom before the law--Winnie Mandela's house. Visitors may walk through the house and witness history through its artifacts, photos, and displays.

In 1958 she married Nelson Mandela. They remained married for 38 years and had two children together. They lived in this house in Soweto. In 1963, after Mandela was imprisoned, she became his public face. During that period, she rose to prominence within the domestic anti-apartheid movement.

Mandela was released from prison on February 11, 1990, and the couple separated in 1992. Their divorce was finalised in March 1996. She visited him during his final illness.

Mandela married his third wife, Graca Machel, in 1998 when he was 80.

The story of Winnie and Nelson Mandela in this house is best

exhibited by the bullet holes left over from decades of government suspicion, surveillance, harassment, oppression and imprisonment. The Mandelas survived it all to see liberation of the Black majority and the end of Apartheid

While Nelson was in prison, police attacked the house because of Winnie's political involvement. Winnie and family members used to hide behind a wooden wall for safety while shots were fired.

In 1970 she went to prison for 500 days, and then was confined to the house for 12 hours a day. Below is a photo of that period after her imprisonment.

Winnie was a professional social worker who fought for justice. From time to time she was detained by apartheid state security services, tortured, subjected to banning orders, and banished to a rural town. She spent several months in solitary confinement in the Pretoria Central Prison.

Winnie was a member of the African National Congress (ANC) and she served the new post-Apartheid government in various positions including as a member of Parliament from 1994 to 2003 and as a deputy minister of arts and culture from 1994 to 1996. She served on the ANC's National Executive Committee and headed its Women's League. Madikizela-Mandela was known to her supporters as the "Mother of the Nation".

Frederik Willem (F.W.) de Klerk's photo is also on display. He served as state president of South Africa from 1989 to 1994 and as deputy president from 1994 to 1996. As South Africa's last head of state from white-minority rule, he and his government is responsible for dismantling the Apartheid system and introducing universal suffrage. After the oppressive and stepped up militarism of the P.W. Botha government, de Klerk recognized that growing ethnic animosity between the Xhosa and Zulu people as well as violence, and human rights abuses was leading

South Africa into a racial civil war. He permitted anti-apartheid

marches, legalized previously banned

anti-apartheid political parties, and freed imprisoned anti-apartheid

activists such as Nelson Mandela.

This display case has a collection of certificates, photos, and artifacts the Mandelas collected over the years before and after Apartheid.

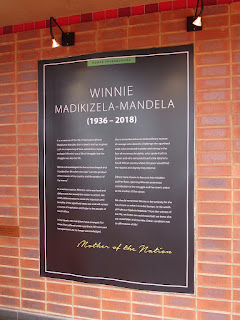

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Mother of the Nation

1936-2018

It is a measure of the life of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela that in death she has ins pired such an outpouring of love, admiration, loyalty and grief. Winnie's was a life of struggle, but the struggle was also her life.

Winnie acknowledged the forces that shaped and moulded her life when she said, "I am the product of the masses of my country and the product of my enemy".

As a woman warrior, Winnie's voice was loud and defiant and she roused the nation to action. her steely determination to resist the injustices and brutality of the apartheid state was and will remain a source of inspiration and hope to the people of South Africa.

In her death, two narratives have emerged. For those that suffered under apartheid, Winnie's past transgressions are no longer acknowledged.

She is remembered as an extraordinary woman of courage who dared to challenge the apartheid state; who remained resolute and strong in the face of enormous brutality; who spoke truth to power; and who remained true to the ideal of a South African society where the poor would find the respect and dignity they deserve.

Others have chosen to focus on her mistakes and her flaws, ignoring Winnie's enormous contribution to the struggle and her iconic status as the "Mother of the Nation".

We should remember Winnie in her entirety for she has shown us what it is to be human. In the words of Professor Njabullo Ndebele: "From the witness of her life, we knew we could stand tall; we knew also we could falter and stumble. Either condition was an affirmation of life."

Upon the death and state funeral of Winnie Mandela on April 14, 2018, Deji Okegbile wrote an article in his blog. Click below to see the article.

WINNIE MANDELA, MOTHER OF NATION: THE SOUL AND PUBLIC FACE OF ANTI- APARTHEID STRUGGLE

Development of Soweto

Soweto was once a symbol of the united resistance against the racist apartheid white government. It was home to the anti-apartheid leaders Nelson and Winnie Mandela and Bishop Desmond Tutu. Today, Soweto is home to 1.3 million people, one-quarter of Johannesburg's population, the largest Black township in the city.

Originally built in the 1930s, the white South African government designated Soweto a separate township in southwestern Johannesburg for Blacks. The area was an amalgamation of shantytowns and slums that housed rural Black laborers, especially between World Wars I and II. Growth was haphazard and residents lacked services, infrastructure, and governance, however, slum clearance and permanent-housing programs began there in 1948.

A Community Council of Black residents, first elected in 1978, was nominally responsible for developing transport, roads, water supply, sewerage, electricity, and housing. After Apartheid in the mid-1990s these services came under the jurisdiction of the Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council. In 2000 the Greater Johannesburg administrative structure was decentralized into 11 regions where services became the responsibility of each region.

Since Apartheid, Soweto has changed drastically. Housing has been expanded, streets are paved, electricity runs through every house, there are 30 shopping malls, a reliable bus rapid transit system, Uber, minibus taxis, and trains operating every day. Soweto Theatre hosts drama, music and dance productions, as well as festivals, conferences and community gatherings. The Soweto Hotel or several B&Bs host travelers, there are bicycle tours and walks along the Soweto heritage trail, quad biking, tuk-tuk trips and street soccer sessions. Soweto even has the Ubuntu Kraal Brewery, home of Soweto Gold, Orlando Stout and 76 Jameson.

Then there is Vilakazi Street, the main drag, that most tourists see. It

is safe, clean, under constant police patrol,

and vibrant with shops, restaurants, singers and dancers, the Winnie

Mandela Museum (the former house of the Mandelas), and nice houses,

including Bishop Tutu's. It also gives the impression that Soweto is doing just fine.

Vilakazi Street is the only street in the world where two Nobel prize winners once lived: former president Nelson Mandela (see below) and Archbishop Desmond Tutu (left). Not far from the street is Trevor Noah's boyhood home.

However, as Niq Mhlongo reports in a 2019 article in The Guardian, Vilakazi Street is a stark contrast to the rest of the

township that is crippled with poverty, drug addiction, and crime.

"This other Soweto is modern and sophisticated in places, but also blighted by poverty, unemployment, drug addiction and crime. Poverty can be seen in the dirty rusted roofs of the Kliptown squatter camp to the south-east and the Jabulani hostel below, built as dormitory accommodation for migrant black workers in the 1950s. Down the street you might see police chasing a stolen car, or a crowd that has gathered around a victim of mob justice. Addicts of the notorious cheap drug nyaope – a cocktail of low-grade heroin, cannabis and sometimes anti-retroviral drugs or rat poison – are everywhere: in parks, at the traffic lights, outside shops."

Mhlongo contends that the gentrification of Soweto covers the "scars of Apartheid" that not only existed between whites and non-whites but between African tribes and ethnic groups.

In the old days under Apartheid, Soweto was divided into traditional African tribal groups: Zulu, Pedi, Shangani, Swati, Venda, Xhosa, Tswana, Sotho and Ndebele. People lived by each tribe's ethnic rules and customs. In this way, Apartheid deliberately designed competition and ethnic hatred among the different groups.

Today there are class divisions, according to a 2019 article in the New York Times. Many in Soweto have built multiple shacks in their backyards to rent them to families who can't find housing. Some roads that were paved after Apartheid are crumbling--or they were missed. Electricity is cut off to those who can't pay their bills. Unemployment is high with over half of those under 35 jobless. Much of the economy is still run by South African white people or those outside the country. Many of South Africa's new leaders are corrupt and lining their own pockets instead of helping the Black majority from whence they came.

Electricity remains a big issue today. In the 1980s it united people against Apartheid by refusing to pay for it. Today, more than 80 percent of Sowetans do not pay for electricity. However, today this issue divides the country's leaders and the Black majority, most of whom remain poor.

Cyril Ramaphosa, a successful businessman and current South African president since 2018 once lived in a house with no electricity. He fought against the Apartheid government for not providing electricity to Sowetans.

After the end of apartheid, this culture of nonpayment continued. Today, more than 80 percent of Sowetans do not pay for electricity.

But while nonpayment unified Sowetans in the 1980s, today it helps divide the country’s leaders and their base.

“The days of boycotting payment are over,” Ramaphosa, said in June 2019. “This is now the time to build. It is the time for all of us to make our own contribution.”

However, many poor South Africans believe electricity should be free, or at least heavily subsidized. They feel betrayed by Ramaphosa's corruption and the ANC.

Meanwhile, opportunity in South Africa is not as open or evenly distributed as some who have succeeded believe. As usual, those who have made it disparage those who haven't.

“We all had the same opportunities, why didn’t you take yours?” Dumisani Bengu, 47, a banker, said to an imaginary critic. “We all grew up in the same space, but I persevered at school.”

Businessman, Bongani Moyo, 45, who runs a construction firm, believes that some people have had opportunities for success while other people haven't.

“But some of us also had to find our way and get ourselves out of a rut," said Moyo, "and others didn’t get an opportunity at all.”

The houses in Soweto illustrate this economic divide. Those houses on the left are signs of success while those on the right, a majority of people, have not been as fortunate. One of Mandela's goals in his administration as president was

to improve housing. He tried but didn't succeed as much as he had hoped.

Because there is not much industrial development in Soweto, most township residents commute to other parts of Greater Johannesburg for employment. You see them crowded in vans like these.

Small entrepreneurial businesses

have become a source of income for some people in Soweto. Many are taking advantage of the growth of tourism.

Tourism has become another viable business venture in Soweto. Vilakazi Street is the center of tourism, but quite unlike most areas of the township.

We had lunch at Sakhumzi, a popular buffet restaurant on Vilakazi Street. One side of the building opens up to the street, and small groups of men sing and beg for tips

Among the tourism businesses

were small groups who performed "native dances". They seem to

titalate visitors' images of Africa. Photographers also abound. They capture people walking on Vilakazi Street or dancing with various "native" groups.

Orlando Towers

In 1942, as the population and energy consumption of Johannesburg grew, British engineers constructed the Orlando Power Station in Soweto. The coal plant successfully ran until 1998 when it was decommissioned. The building collapsed in 2014, but the station’s two cooling towers remained--and were decorated.

The towers exhibit another

tell-tale sign of Apartheid. The plant originally generated electricity for the white residents

of Johannesburg, but not for the Blacks and non-whites who lived right next to it in Soweto. Today, the electricity is shared among all citizens of the big city.

The drab cooling towers remained after the power plant closed. Both towers were then painted with pictures of soccer, music, fashion,

and historical figures to signify the town's cultural renaissance. In the words of local resident Tshepo Motsepe, Orlando is the “quintessence

of the township, intertwining urban culture, history and heritage,

communal living and camaraderie, a techno-savvy population, and social

amenities.”

The drab cooling towers remained after the power plant closed. Both towers were then painted with pictures of soccer, music, fashion,

and historical figures to signify the town's cultural renaissance. In the words of local resident Tshepo Motsepe, Orlando is the “quintessence

of the township, intertwining urban culture, history and heritage,

communal living and camaraderie, a techno-savvy population, and social

amenities.”

Since 2009, the towers have become THE place for bungee jumping. After being lifted over 300 feet

in the air, jumpers walk across a narrow bridge connected

between the two towers and bungee jump, abseil,

free-fall, and power swing. This is tourism at its best!

2010 FIFA World Cup

Not far from Soweto was the Soccer City Stadium that held the opening and final matches of the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Nelson Mandela, 92, attended the last match where he was hailed as South Africa's hero.

About 85,000 people attended. Guests included Archbishop Desmond Tutu, former UN secretary general Kofi Annan, Spain's Wimbledon tennis champion Rafael Nadal, supermodel Naomi Campbell, South African-born actress Charlize Theron and American actor Morgan Freeman, who played Mandela in the recent film Invictus. Sixteen heads of state were reportedly present including Zimbabwe's Robert Mugabe.

Danny Jordaan, the tournament's chief organiser, was quoted in The Guardian -- July 11, 2010 about the significance of the event.

"Just 20 years ago we were a society entrenched on a racial basis by law. Black and white could never sit together in stadiums, go to the same school, or play in the same football team. Within 20 years, we saw white supporters having their faces painted in the Ghana colours, supporting young Africans.

"That's something this World Cup has brought: nation building and social cohesion. People walked tall. They were very proud of this country. They were told over many years, you are inferior, you cannot do these things because of our history. So that was a psychological barrier the nation crossed: the world is saying this may be the best ever World Cup and this was an African World Cup."

Shakira - Waka Waka (This Time for Africa) (The Official 2010 FIFA World Cup™ Song)

Johannesburg was a difficult place to visit. I felt a certain discomfort knowing a little of its history. And yet, as I research and write about the city for this blog, I have grown in curiosity and respect for the incredible courage and accomplishment of so many people over several decades. We can only hope and pray for South Africa to continue its journey of peace and justice knowing that the road to equality remains a struggle each day and each year by each person.

Our guide, who lived through the Apartheid era until he was 17 years old, was well-informed about the city and its politics and culture. He was also more than willing to take photos of us travelers. He was probably one of the lucky ones to have a good job even though he was all too familiar with the plight of the majority people of Johannesburg.

No comments:

Post a Comment